I think the word "plasma" is officially broken. It’s useless. Done. Stick a fork in it. This week, my news feed has been a firehose of the word, and not a single instance had anything to do with the others. One minute I’m reading about scientists creating a literal star in a magnetic bottle, the next I’m seeing warnings that a medical device might accidentally kill you with cold blood, and then I’m getting whiplash from a story about Canadian good intentions getting sold off to a Spanish pharma giant.

It’s like the universe is running a psychological experiment to see how many contradictory definitions for a single word a person can handle before their brain just short-circuits. We’ve got fusion plasma, blood plasma, crypto plasma, and probably some new-agey wellness plasma that promises to align your chakras for $200 a session. It’s exhausting. And honestly, I think the confusion is the point.

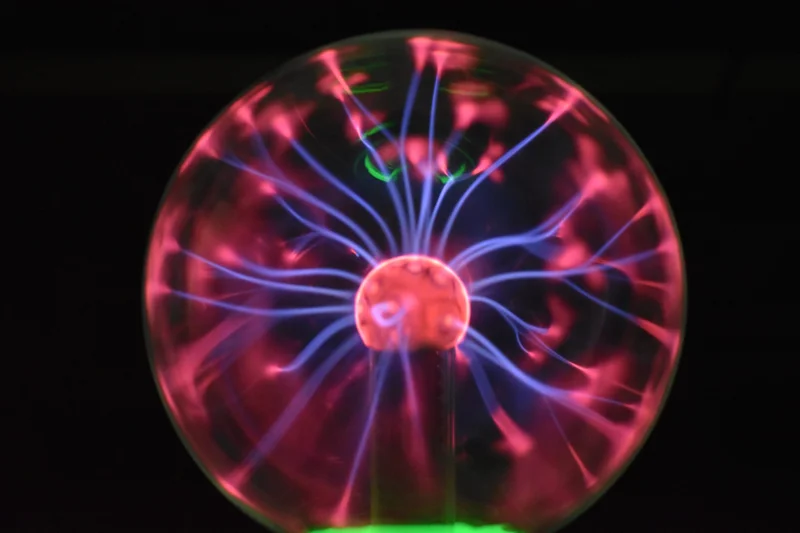

Let’s start with the cool one. The Joint European Torus, or JET. For 40 years, this thing was the pinnacle of our sci-fi fantasies—a tokamak, a doughnut-shaped machine that cooked hydrogen gas until it became the same stuff that powers the sun: plasma. It even broke its own fusion energy record right before they shut it down for good in 2023. Now, the UK Atomic Energy Authority is sending in robots to pick apart its radioactive guts, studying the beryllium and tungsten tiles that stared into the abyss of a man-made star. They’re literally studying the wreckage of our best shot at clean energy to figure out how to build the next one. That’s the "plasma" of our dreams. It's abstract, powerful, and safely locked away in a lab.

Then you get the other kind of plasma. The kind that’s inside you right now.

3M, the company that makes everything from Post-it Notes to industrial-grade adhesives, is "correcting" its Ranger Blood/Fluid Warming System. "Correcting" is a fantastic piece of corporate doublespeak. What it actually means is the FDA has slapped this thing with its most serious recall notice because it doesn't, you know, actually warm blood and blood plasma properly at the flow rates it promised. The machine is supposed to keep you from getting hypothermia during a transfusion; instead, it might just be the thing that gives it to you. The risk, and I’m quoting here, includes "serious adverse health consequences, including… death." Blood and Plasma Warming Device Correction: 3M Company Issues Correction for Ranger Blood/Fluid Warming System

This is a bad idea. No, 'bad' doesn't cover it—this is a five-alarm dumpster fire of corporate negligence. How does a medical device that fails at its one and only job make it to market? Did anyone in a lab coat bother to crank up the flow rate and stick a thermometer in the output before shipping these things to hospitals? The whole situation is a perfect metaphor for the disconnect: we can contain a 100-million-degree ball of fusion plasma, but we can’t seem to build a reliable heater for the plasma that keeps us alive.

If the 3M story doesn't make you cynical enough, let's hop over to Canada. This is where the meaning of "plasma" gets really slippery, and frankly, infuriating. You’ve got people like Peter Johnson and Mike Horgan, guys who show up every single week to a plasma center to donate plasma. They sit there for hours while a machine separates the straw-colored liquid from their blood, and they do it for the purest of reasons: to help people. They believe they are contributing to a national, non-profit system.

Turns out, that’s not quite the whole story. Canadian Blood Services, the agency managing the supply, cut a deal with Grifols, a massive for-profit pharmaceutical company. At first, the line was that Grifols plasma collection was just to make a specific drug for Canadians. When reporters asked what happened to the valuable byproducts from the process, the official answer was that they were being thrown out.

Except they weren't. On an investor call—because offcourse that’s where the truth comes out—the Grifols CEO announced they were using those Canadian byproducts to manufacture a product called albumin for sale on the international market. The donation of a Canadian citizen, given freely with the intent to help a neighbor, is being processed by a foreign multinational and sold for profit to someone else entirely. Blood donors surprised Canadian plasma products being sold abroad. Canadian Blood Services now admits this is happening, claiming the revenue "offsets the cost" of buying other medicines.

This is like donating your old car to a local charity for a family in need, only to find out the charity sold it to a dealership, which then flipped it for a huge profit and gave the charity a coupon for a free oil change. The fundamental trust is shattered. Donors were kept in the dark about where a literal piece of their body was ending up. What does "consent" even mean in a situation like this? These donors aren't thinking about the plasma membrane function of their plasma cells; they're thinking about saving a life, and the system is taking advantage of that goodwill. They walk into a clinic thinking they're performing a civic duty, and walk out as an unwitting supplier for a global commodities business. And for the life of me, I can't understand why a national health service would need to get in bed with a for-profit company that seems to be pulling a classic bait-and-switch.

It’s a mess. People are rightly asking questions, and the answers are buried under layers of corporate PR and vague contractual arrangements. They expect us to just trust them, and honestly...

At the end of the day, the chaos around the word "plasma" isn't just a linguistic quirk. It’s a feature, not a bug. When one word can describe the fuel for a star, the liquid in your veins, and a crypto token, it becomes meaningless noise. And in that noise, it's easier for a company like 3M to issue a "correction" instead of admitting a deadly failure. It's easier for an organization like Canadian Blood Services to obscure the line between altruism and profit. The confusion serves the powerful, not the people donating their time or the patients relying on a working machine. One plasma promises a limitless future; the other is a finite, precious resource being exploited. And we’re left trying to figure out which is which.