I want you to close your eyes for a moment. Imagine you’re standing on the warm asphalt of the Pomona Fairplex. The Southern California sun is bright, but it’s filtered through the low, resonant hum of hundreds of engines. You can smell it, can’t you? That unique cocktail of tire polish, high-octane fuel, and grilled onions from a food stand somewhere. This isn’t just a car show. This is a cathedral of creation.

This was the scene at the Grand National Truck Show, and at its heart was a machine that was more of a sculpture, a 1941 Willys pickup painted a blue so deep you could fall into it. When it was named the World’s Most Beautiful Truck, it was more than just an award. It was a testament to a story. The owner, Larry Jacinto, used to ride in the bed of that very truck as a little boy when it belonged to a family friend. It took him four decades to finally buy it. The build was started by one legendary craftsman, Bob Bauder, and after his passing, finished by another, the Veazie Bros.

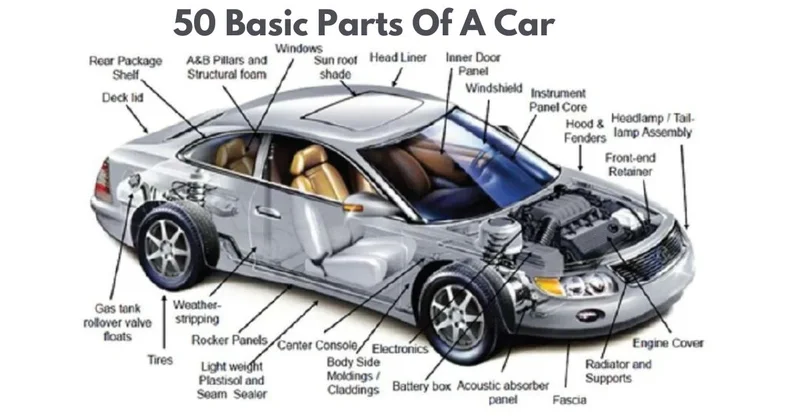

This truck isn't just a collection of `car parts`; it's a physical embodiment of memory, legacy, and human passion passed from one hand to the next. It’s a story of resilience. And I believe it holds the key to solving a crisis that is quietly brewing under the hood of our entire modern world.

While the crowds in Pomona were celebrating this pinnacle of craftsmanship, a different kind of headline was rippling through the financial wires, one that read: "Auto Parts Supplier's Bankruptcy Spells Potential Trouble for Loads of People Who Own a Car, Truck, or SUV." On the surface, it’s a dry business story. A massive company called First Brands Group, the invisible giant behind names you see every day at `Autozone` or `Napa Car Parts`—Fram filters, Raybestos brakes, Autolite spark plugs—filed for bankruptcy. But this isn't just about one company. It’s a profound warning. It’s the sound of a pillar cracking in the foundation of the industrial model we’ve taken for granted for a century.

The Brittle Bones of a Giant

What happened to First Brands? The simple answer is that it stopped paying its bills. Its "Days Beyond Terms"—in simpler terms, how late it was paying its suppliers—was nearly four times the industry average. It was a slow, agonizing bleed-out. But the why is what should grab every single one of us. This company was a monolith. It was a central hub, a single point of failure responsible for an astonishingly vast swath of the `auto parts` that keep our lives moving. From the `car battery` that starts your morning commute to the `honda parts` for your daily driver, its collapse threatens to create supply-chain chaos we haven’t seen since 2020.

When I first read about the sheer scale of the First Brands collapse, and how it connects to a local story out of Louisiana where a single dealership owner failing to provide titles has thrown dozens of lives into chaos, I honestly felt a chill. It’s the same pattern, a fractal of fragility, repeating at every scale. We have built a world that is incredibly efficient but terrifyingly brittle, a system of giants where one stumble can cause a seismic shockwave. We’ve become utterly dependent on these vast, faceless, centralized systems for the most essential `parts of a car`, and we’re just now realizing how fragile they are.

This is the old way. A top-down, opaque system where the connection between the maker and the user is stretched across oceans and balance sheets until it’s invisible.

But what if the answer isn’t a bigger, better giant? What if the answer was already there, gleaming under the lights in Pomona?

That 1941 Willys, with its blown LS3 motor and Ron Mangus interior, is more than just a beautiful truck. It’s a symbol of a different model. A decentralized, passion-driven, human-scale model of creation. It wasn't built by a vast, anonymous supply chain; it was built by people with names, with workshops, with a legacy. This is the seed of a powerful new paradigm, one where technology could empower a million local creators instead of just a few global giants—the speed of this is just staggering—it means the gap between the world of First Brands and the world of the Veazie Bros. is closing faster than we can even comprehend.

Think of it like this. The centralized parts industry is like the world of medieval scribes, where knowledge was held by a few and painstakingly copied. The Grand National Truck Show, full of individual creators and custom fabricators, is the first spark of the printing press. It’s a demonstration of what happens when the tools of creation are put in the hands of the passionate.

Now, what happens when we supercharge that passion with the technology of tomorrow? When you can 3D print high-strength `replacement car parts` in a local shop? When AI can help you design a custom `car body part` that perfectly fits your vision? When looking for `car parts near me` doesn't just mean a big-box store, but a network of local artisans and micro-factories?

This is not a distant fantasy. It’s the next logical step. We are on the cusp of a manufacturing renaissance. The bankruptcy of First Brands isn't the tragedy; the tragedy would be trying to rebuild the same fragile system. The opportunity is to build something new. Something more resilient, more human, and infinitely more inspiring. Of course, with this power comes responsibility. A decentralized world needs new systems for ensuring quality and safety, a challenge we must meet with the same ingenuity we apply to the creations themselves. But the path is clear.

So, what future do you want to build? One where your ability to repair your own vehicle is dependent on the solvency of a distant, fifty-billion-dollar corporation? Or one where it’s supported by a vibrant, local ecosystem of creators, makers, and innovators? The choice is becoming clearer every day.

The blueprint for the future of making things isn't sitting in a corporate boardroom. It’s in Pomona. It’s in the passion of a man who waited forty years for his dream truck, in the hands of the builders who brought it to life, and in the community that gathered to celebrate it. The old industrial machine is failing, not because of a single bankruptcy, but because a better idea has already been born. We’re not just on the verge of a new industrial revolution; we’re on the verge of a creative one. And it’s going to be beautiful.

Reference article source: